In our Bang for your Buck series, we talk about product features and component designs that offer increased value and performance. We’ve discussed source units and speakers, and now it’s time to take a deep look into amplifiers and what separates one amplifier from another.

In our Bang for your Buck series, we talk about product features and component designs that offer increased value and performance. We’ve discussed source units and speakers, and now it’s time to take a deep look into amplifiers and what separates one amplifier from another.

Years ago, a prominent mobile audio enthusiast claimed that all amplifiers sound the same under strict test conditions. He even backed up the statement by offering a large cash reward to anyone who could pick one amp 10 times out of 10 under controlled listening tests. While there is value in his claim and it would be very hard to determine the difference between two amplifiers in blind testing 10 out of 10 times, that doesn’t mean that all amplifiers are the same. In fact, there are some big differences.

This articles focuses on two widely different areas of performance that many manufacturers refuse to discuss in detail: distortion and noise.

Is Power Important?

Does the ability of one amplifier to make more power than another determine its quality or performance capabilities? Well, if the less-powerful amplifier is driven into distortion, then certainly the more-powerful amplifier will sound better. While they’re operating within their rated power ranges, though, does maximum power matter? Not so much.

What’s this Damping Factor Thing?

For decades, manufacturers of high-end amplifiers have provided damping factory specifications. This number is a ratio of the output impedance of the amplifier to a specified load impedance. The story goes that an amplifier with a higher number would produce a tighter, more-controlled sound because the low impedance of the amp would short the back-EMF signal from the speaker.

For decades, manufacturers of high-end amplifiers have provided damping factory specifications. This number is a ratio of the output impedance of the amplifier to a specified load impedance. The story goes that an amplifier with a higher number would produce a tighter, more-controlled sound because the low impedance of the amp would short the back-EMF signal from the speaker.

Depending on your version of physics, the damping factor can be a large number, or a very small one – making it potentially relevant or a complete red herring.

For solid-state amplifiers, the damping factor or output impedance ratio is high enough that the load impedance has very little effect on the resulting frequency response of the system. For tube amplifiers with impedance-matching transformers, this isn’t always the case. Worrying about, or even considering, the damping factor is way down the list of concerns.

Background Noise

We’ve talked about signal to noise ratio in detail in our discussion of head units. It’s a big deal in a discussion of amplifiers and will rear its head again when we talk about signal processors.

Any electronic device creates unwanted noise when a signal passes through it. Even something as simple as a resistor creates a small amount of noise. In this example, it’s likely too small to be audible – but it’s there. In a complex circuit with gain (an increase in signal amplitude), creating unwanted noise is a common byproduct of questionable design.

Any electronic device creates unwanted noise when a signal passes through it. Even something as simple as a resistor creates a small amount of noise. In this example, it’s likely too small to be audible – but it’s there. In a complex circuit with gain (an increase in signal amplitude), creating unwanted noise is a common byproduct of questionable design.

How does noise manifest itself in an amplifier? It’s the background hiss you hear from your speakers when no music is playing. Ideally, you don’t want any noise adding content to your music.

If you have those really efficient PA speakers, then choosing amplifiers with excellent noise specifications is crucial. The speakers themselves offer 5 to 10 dB more output for a given input signal, so any noise that is present will be 5 to 10 dB louder.

Signal to Noise Ratio Specification

We’ve covered this before, but we are going to do it again now because it’s important. There are two ways manufacturers publish SNR or S/N Ratio specs: either rated to a specific output level (1 watt into 4 ohms) or relative to the maximum power production capabilities of the amplifier. You can’t compare the two directly, but you can estimate.

Let’s look at two full-range amplifiers. In this example, we’ll use a pair of similarly rated four-channel amplifiers. Amplifier A has a S/N Ratio published at -104 dB and amplifier B amplifier rated at -88 dB. Assuming the numbers are published using the same standard, amplifier A produces 16 dB less noise than amplifier B. Unfortunately, in this example, the -104 specification of amplifier A is published related to its rated power, while amp B is relative to 1 watt of output. Using the same specifications, amp A produces -84 dB of noise, 4 dB more than amp B.

Distortion Considerations

Distortion is, in the simplest of terms, the addition of unwanted information to a signal. Just as with noise, all electronic devices add some amount of distortion to signals as the signals pass through. In most cases, unless something has gone very wrong, the original signal passes through the device unchanged. Distortion is generated by the addition of unwanted information.

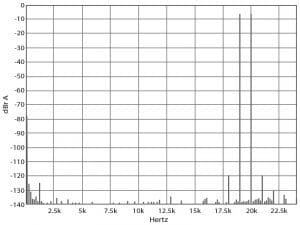

Harmonic distortion is the addition of multiple instances of the original signal. Many high-end home amplifiers are tested using a 50 Hz tone at rated power. Analysis of the resulting spectral content shows just how much unwanted information is produced.

The image above shows amazing performance from a very high-end solid-state home amplifier. As you can see, there is a little bit of 150 and 175 Hz content, but it is at almost -120 dB below the stimulus signal.

The image above shows amazing performance from a very high-end solid-state home amplifier. As you can see, there is a little bit of 150 and 175 Hz content, but it is at almost -120 dB below the stimulus signal.

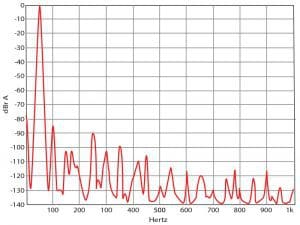

In this example, we can see the harmonics created in a high-end home audio Class D amplifier. A 100 Hz signal is present at a level of -85 dB and a 250 Hz signal is present at a level of -90 dB.

In this example, we can see the harmonics created in a high-end home audio Class D amplifier. A 100 Hz signal is present at a level of -85 dB and a 250 Hz signal is present at a level of -90 dB.

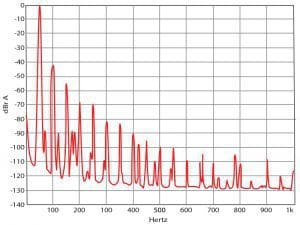

To really highlight the potential for unwanted behavior, we have included the spectral content of a high-end vacuum tube amplifier. You can see that there is spectral content at 100 Hz at a level of -42 dB, 150Hz content at -54 dB and 200 Hz content at -67 dB. This distortion would be audible during listening.

To really highlight the potential for unwanted behavior, we have included the spectral content of a high-end vacuum tube amplifier. You can see that there is spectral content at 100 Hz at a level of -42 dB, 150Hz content at -54 dB and 200 Hz content at -67 dB. This distortion would be audible during listening.

Intermodulation Distortion

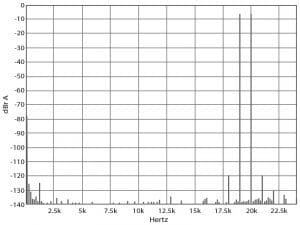

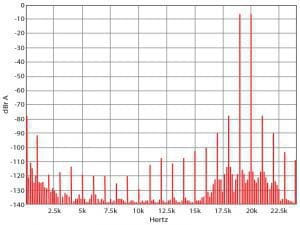

Another kind of distortion is created when two signals passing through an amplifier interact with one another to produce distortion that is the difference between the two signals. The industry standard test for intermodulation distortion is to play a test signal that contains two sine waves – one at 19 kHz and a second at 20 kHz. Two things will happen when distortion is produced using these stimulae: Content will be created on either side of these tones and at a difference between them, i.e., at 1 kHz.

This graph shows a high-end home amp with excellent IMD behavior. The two side-bands are at -119 dB and would be completely inaudible.

This graph shows a high-end home amp with excellent IMD behavior. The two side-bands are at -119 dB and would be completely inaudible.

This graph shows the same Class D as in the discussion of harmonic distortion. It is easy to see that the test stimulae created a significant amount of information. The peak is at -78 dB, so it’s not a complete disaster.

This graph shows the same Class D as in the discussion of harmonic distortion. It is easy to see that the test stimulae created a significant amount of information. The peak is at -78 dB, so it’s not a complete disaster.

Shopping for a Car Audio Amplifier

Since nobody in the mobile electronics industry seems willing to submit their products for this level of scrutiny, how does one go about picking an amplifier that offers exceptional performance? The only way is through extensive listening. A handful of amplifiers on the market offer exceptional performance, and not all of them are expensive. At the same time, some very expensive amplifiers perform poorly.

If you want to find the best, then see if you can borrow that amp in question from a friend and put it into a reference system. If your music suddenly sounds warmer, that’s a sign that there is additional harmonic content. It is “nice” to listen to in some cases, but it is certainly not accurate.

Once you have developed a strong reference for accuracy, you will be able to pick out amplifiers that offer excellent performance. Your local mobile electronics retailer should have a demo vehicle that you can audition. Happy shopping!

This article is written and produced by the team at www.BestCarAudio.com. Reproduction or use of any kind is prohibited without the express written permission of 1sixty8 media.

Leave a Reply